THE WORK OF THE PSYCHOANALYST: REFLECTIONS ON COUNTERTRANSFERENCE WITH INSTITUTIONALIZED YOUTH PATIENTS

AUTHORED BY

*Dr. Ruth Axelrod Praes

**Dr. Benny Weiss Steider

*Lic. Juan Azar Andere

Affiliations:

*Asociación Psicoanalítica Mexicana (APM).

** Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Key words:

adoption, foster care, transference, countertransference, supervision.

Statements:

The patients´ names as well as their personal data were changed or omitted in accordance to international standards to protect their privacy rights and not interfere with legal procedures involved in their possible adoption.

The authorization to publish the clinical material and description of the foster institution involved was provided in written form by the Directive Board of Hogar Dulce Hogar A.C.

There is no conflict of interest in the published material; the work is original and has not been presented to any other forum or editorial board.

All the authors read and approved the written material.

Mexico, 2013

Abstract

In this work we will briefly describe present-day, postmodern evolution of the family and the attention centers that both the government and the private sector have established when this fails. The birth of child psychoanalysis and its application in one of those centers, forging roots for further psychoanalytic development, is briefly described. The importance of countertransference and analyst supervision for those treating traumatized patients left without a family will be discussed, as will an institution that altruistically rescues these children; the function of a psychoanalyst and his/her avatars will be shown by way of three clinical cases when a strong countertransference obviously occurred in him/her. Finally, reflections will be made about the importance of handling countertransference with the analyst´s supervisor.

Introduction

Psychoanalysis has found its way into many areas of life in big cities. Despite the controversies, it maintains lines of reflection, thinking, and treatment for children, adolescents, adults, couples and families.

Psychoanalytic work can be integrated into diverse areas—both on the individual and group level—including schools, medical offices, hospitals, and in this case, an orphanage where the Hogar Dulce Hogar (Home Sweet Home), A.C. Foundation houses over seventy children who have lost their families.

Two child psychoanalysts offer their services in office within this foundation. The staff selects the children who may need psychoanalytic attention, and they are given the possibility of having one session a week on a voluntary basis. After three absences, the patient loses his/her right to continue.

The psychoanalyst confronts multiple challenges—institutional necessities, his/her ethics and patient well-being; there could be a struggle with countertransference, which is one of the means to connect with children. Psychoanalytic supervision allows for the recognition of the unconscious that limits listening and interpretation, becoming the privileged place of translating intersubjectivity and its avatars.

The Family in the Twenty-First Century

After birth control pills invaded the pharmaceutical market in 1959, it was assumed that family planning would permit every woman to decide whether or not to become a mother, when to get pregnant and who would be the father of her children, which is to say, to format her family as she wished. But in matters of hope, disillusionment always appears as an alternative.

The idea that maternity was an instinctive response was discussed for many years; however, response did not remain as instinct, since maternity can be considered a choice. Many women in different countries have acquired more and more rights and responsibility in terms of having control over their bodies, whether it is to gestate or abort, to avoid pregnancy, or maintain their virginity.

Defining the feminine now appears to be an object of choice, interrogation, and arbitration. Almost nothing is established imperatively in the social order; it is a time when everyone invents her own life (Axelrod, 2006), even if Welldon (2006) says that women use their bodies, particularly their reproductive system, as a vehicle for expressing unconscious conflicts. And birth tends to provoke disappointment about the differences between the imaginary and real baby.

It is expected that a group, although not ideal, would offer the possibility of forming a family from the mother, father and their descendants, and that they would have a harmonious life with adequate management of daily events and conflicts, whether they live together or separated. The same would apply for other options such as uniparental, same-sex or extended family households.

In any form, the definition of family includes the possibility of offering its members the mental, physical, economic, educational, work, spiritual, athletic and social well-being that any individual needs to grow—a space not so much subjective as intersubjective—where handling emotions does not reach toxic levels, where alliances are flexible, and laws are clear. Where the law of the father is in place and generational differences clarify the incest taboo, where the oedipal complex allows a transgenerational conformation of gender differences. Unfortunately at the moment, we find a plethora of events where families move away from this ideal and fall apart.

There are many factors distorting a family group that can often alter, break, destroy or upset it, causing expected family functions to fail. The familial system can be disorganized due to aggression—whether it is passive or active—violence, addictions, mental illness and its repercussions, breaking agreements, internal crises in couples, external crises and their consequences, power plays, the rupture of the law, and many other events that leave family members deprived of expected well-being.

Between the real and the ideal, in each persons’ spectrum of oedipal integration and disintegration, the handling of drives and their domestication is interwoven.

When the family framework ruptures and parents or substitute relatives are no longer capable of caring for and living with their little ones, society has created alternatives so that they do not remain homeless.

The History of Orphanages

Since ancient times there has been concern about caring for orphans. In Jewish law, on record in their Bible dating from 2,000 B.C. (as cited in Jewish Publication Society Tanakh, 1985), there is a detailed description of how one should care for and protect orphans. Later, in the fourth century B.C. in ancient Greece, Plato (as cited in Corral, 1871-1872) also described the care of orphans and what type of “psychological” attention should be given to them. The early Christian Church assigned this function to the bishops, which was later delegated to monasteries, subsequently establishing from the Middle Ages on orphanages all over the European continent (Orphans and Orphanages, 2013). It is interesting to note that orphanages have existed in Mexico since 1548 (Steelman, 1907).

In developed countries during modern times, social services administered by the government have made the existence of large orphanages obsolete, favoring foster care instead: homes where substitute parents or institutions are assigned personalized care in exchange for certain pay. Even in these countries the magnitude of the problem is large; since the year 2000 there have been over 500,000 children assigned to foster care in the United States alone (Foster Care, 2013), children who were orphaned, abandoned by their parents or removed from their homes due to abuse or negligence, or who simply escaped from violent situations, without taking into account those who due to physical or mental deficiency required special attention that their parents were unable to provide.

Conversely, in developing countries like Mexico social responsibility is so great, due to the enormous quantity of orphans or abandoned children, that efforts are insufficient in these places; therefore, orphanages continue to exist, generally with less than one hundred children, administered by religious congregations or charity foundations (Sideso, 2013). Since many of these orphanages receive governmental funds or private donations, the administrators may misuse these funds or abuse the children (Orphanage, 2013).

One of the reasons why large orphanages went by the wayside is because in such overcrowded places each child received inadequate personal contact and affection, which is absolutely necessary for proper mental development. Crowding had to do the desire to care for the greatest number of children possible and the exploitation or management of orphanages for profit. Nevertheless, particularly in developing countries, there are foster care institutions that provide infants with an adequate environment for their development in an exemplary and altruistic manner; they put together administrative boards and foundations whose goal is to maintain the institution using the supplies provided by private donations in the strictest and most adequate way possible (Hogar Dulce Hogar, 2013).

Historically, human development has frequently caused wars where a high percentage of individuals perish. These situations mean that many children are orphaned and in need of care. Due to perennial wars and conflicts in different parts of the world, millions of children do not have social or personal attention. In only the last world war more than 50,000,000 people died (World War II Casualties, 2013) and several million children were orphaned in Europe alone (Orphans, 2013). It was precisely in this war, in 1938, that Sigmund Freud had to escape Nazi persecution and immigrate to London with his daughter Anna.

The First Child Psychoanalysts

The war gave Anna Freud the opportunity to observe the effect of deprivation of parental care on children. She set up a center for young war victims called The Hampstead War Nursery (Freud A, 1945). Here the children got foster care, although mothers were encouraged to visit as often as possible. The underlying idea was to give children the opportunity to form attachments by providing continuity of relationships. It could be said that Anna Freud was the first psychoanalyst to work in an orphanage or foster home. This was continued, after the war, at the Bulldogs Bank Home, which was an orphanage run by colleagues of Freud that took care of children who survived concentration camps (Freud A, 1942). Based on these observations Anna Freud published a series of studies on the impact of stress on children and the ability to find substitute affections among peers when parents cannot give them (Freud A, 1973a).

During the 1970s Anna Freud was concerned with the problems of emotionally deprived and socially disadvantaged children, and she studied deviations and delays in development. At Yale Law School, she taught seminars on crime and the family. This led to a transatlantic collaboration on children and the law published as Beyond the Best Interests of the Child (Freud A, 1973b). There was no doubt that children deprived of emotional attachment developed certain pathologies such as depression, suicide attempts, eating disorders, post-traumatic stress and violent behavior, among others, and that their neurological development was compromised. Statistically speaking, it has been found that orphans—even those coming from excellent foster care homes—have more compromised social development to the degree that less than 2 percent graduate from college (Foster Care, 2013) and many of them present violent personalities such as the so-called unwanted child syndrome (Feder, 1975).

While Anna Freud was the first psychoanalyst involved in foster care centers, Melanie Klein was simultaneously, and successfully, applying psychoanalytic techniques with children. She became aware of the great importance in mental development of the first relationship children have with significant figures; as such, she pioneered object relations theory in psychoanalysis.

Anna Freud developed the psychological principles of the ego and other defense mechanisms by basing her observations on infants (Freud A, 1927) adapting to exterior challenges, while Melanie Klein established the enormous importance of stabilizing figures in child development by applying psychoanalysis to infants (Klein, 1932).

The differences between treatment approaches for children, and therefore psychoanalysis in general, of Anna Freud and Melanie Klein, caused great conflicts that in their time divided psychoanalysts into two antagonistic groups continuing to this day (King, & Steiner, 1991), although a neutral or independent group was formed known as the Middle Group (Rayner, 2000). These groups are the basis for child psychoanalytic treatment. For Anna Freud the analyst should not only be an interpreter of the child´s transferences over time, but also his/her teacher (Freud A, 1927; Holder, 2005), since it is in this stage that she supposed the superego was still immature and in need of strengthening. While for Klein there is a primitive superego that was considerably strong and severe, which is the basis of neurosis and therefore the goal of the analyst was to mitigate that severity (Klein, 1926.) While for Klein the superego comes into existence during the first year of life and there is a need for it to be mitigated, for Freud it is still immature and in need of strengthening. Both Anna Freud and her father agreed that the superego was structured by way of the overcoming of the oedipal complex (Freud S, 1923). Klein considered that the superego exists from the oral and anal stages and is difficult to modify, as opposed to what happens with the ego (Klein, 1928). Therefore for Freud (1905) the oedipal complex arises between three and four years of age, which is resolved between five and six years of age; while for Klein it exists from pre-genital stages and does not depend on later resolution for personality formation.

Psychoanalysis in Foster Care Institutions

In the opinion of Sigmund and Anna Freud and Melanie Klein, affectionate relationships in the first stages of a baby´s life are essential for balanced development of the human psyche. As such, an abandoned child is synonymous with a child seriously lacking in emotional development. When an infant is deprived of the love and care of its parents or close significant figures, what role does the analyst play? Was he or she taken as the paternal or maternal figure where the formation of the superego and the overcoming of the oedipal complex would take place? Or is the analyst a stabilizing figure in which the child will strengthen his/her ego and superego?

Adopted children, whether they stay in a home permanently or transitionally—in an orphanage or foster care—tend to have suffered from violence. While some did not have their parents as significant figures in their development, others had them present in traumatic ways.

There has been little psychoanalytical work done in foster care institutions; notwithstanding, interesting attempts have recently been made (Clausen, Ruff, Von Wiederhold and Heineman, 2012) where the benefits achieved for these children based on prolonged treatment with the same therapist are described. This is based on the specifics of a child’s earliest relationships, and how the nature and quality of a child’s attachment during the early years, shapes the character of relationships throughout life (Bowlby, 1969). They postulate that psychoanalytic treatment can revisit, re-create, and even reshape early attachment experiences.

Nowadays family violence represents an enormous social obligation; if the organizations overseeing foster care are responsible for children likely to resort to this kind of behavior, the therapist´s role takes on a great deal of importance. It is very probable that investment in psychological attention for foster care children is less burdensome than the damage caused from not having it. Under these circumstances, the function of the psychoanalyst, precisely in charge of readjusting lacking attachments in orphans, has a preponderant role. Due to the high cost of psychoanalytic intervention, psychodynamic techniques, such as brief psychoanalytic therapies, can better suit these needs more so than those of proper analysis.

It is worth mentioning that Casamadrid (2001) considers it substantially beneficial for adopted children to work with the fantasy of the family novel (Freud, 1909). By elaborating on the fantasy of the novel itself, the children substitute the father or the mother for other superiors to be free of the parents´ or significant others´ authority. In these children, this traumatic situation in not just a fantasy; the fantasy has aspects from reality that will affect its elaboration.

Achieving the integration of the mother, split between bad and good, is a difficult process that takes time to carry out, but the psychic effort required by the adopted child is much greater. The presence of two pairs of parents makes it difficult to integrate the good and bad mother in one, complicating further identifications and the formation of the superego (Brinch, 1980).

Some frequent characteristics of the adoptee´s self are: fear of fragmentation, basic feelings of anxiety, retreat into fantasy, perception alteration, and negation as a predominant defense mechanism. These are alternatives to be addressed in the analytical transference space.

A history with no prehistory, a future with no past, analytical work is a new alternative to get inside these conflicts.

Due to the young age of some children in foster care institutions, play techniques can be employed, the use of which has been reported since 1919 by M. Klein (1955), later by D. Winnicott (1968, 1971) and recently applied in these types of centers (Akhtar, M. 2012, & Clausen, J. M. 2012).

Countertransference

The discovery of the mechanism of counter-transference was made by S. Freud when he began to look at the analyst’s perspective in the therapeutic relation, which he describes in the paper “The Future Prospects of Psychoanalysis” (Freud S., 1946), the same year that he founded the International Psychoanalytical Association. Countertransference was then described as the emotional reaction to the patient’s stimuli due to the influence of the patient’s feelings on the analyst’s unconscious feelings. Freud understood it as an obstacle to the progress of analysis and, as such, to be removed. This was until 1950 the most commonly accepted conception of countertransference; when Paula Heimann’s ideas together with those of Heinrich Raker (1951) and Margaret Little (1951) became widely known, this mechanism started to be seen as an important aid to understanding the patient. Klein always rejected that perspective and remained close to Freud’s ideas even though she recognized it as a diagnostic tool. The works of Wilfred Bion (1967) and Money-Kyrle (1955) showed that, along with the concept of projective identification clearly defined by Klein, countertransference was a valuable tool for understanding the patient in both its pathological and benign forms.

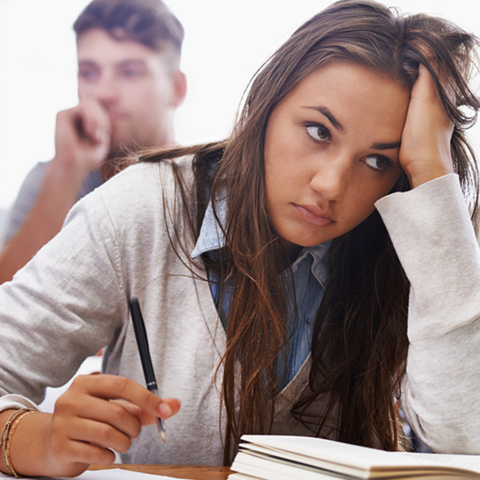

Some of the difficulties confronted by the analyst in an orphanage or foster care situation are that she/he can see the child once a week at the most. According to A. Freud and M. Klein, these circumstances generate possible intense countertransference in the therapist, since the infant tries, in that limited time of attention, to take the analyst as an object of psychic anchorage; she/he not only seeks to express his/her desire for love, but also for violence, products of death and life instincts, that according to Klein (1932) and following S. Freud manifest in different developmental stages of the psychic apparatus (Freud, S. 1955). With respect to this, an enormous death or destructive instinct that goes beyond that of love or conservation can be confirmed in abandoned or abused children.

As such, many of these children develop violent personalities and others direct these instincts inward; it is a known fact that suicide occurs at a higher rate in these individuals in comparison with those who had an adequate relationship with their parents or significant figures (National Center for the Prevention of Youth Suicide, 2013; Krakowski, 2004). In analytical work with this population the countertransference that occurred in sessions with children is therefore very intense, particularly in those who did not have the constant presence of parents or significant figures.

Velasco (1996) defined countertransference as all the reactions of the analyst before the patient that can help or impede treatment; they are conscious and unconscious experiences of the analyst. Heinmann (1950) called them total experiences, which include all thoughts and feelings as a reaction to therapeutic interaction, allowing him/her to think about the clinical utility of these experiences to comprehend the patient.

Tubert (2013) mentions that psychoanalysis has two strongholds that validate it: the hermeneutic, because it is founded on the interpretation of hidden meaning that lies beyond apparent manifestations of the patient, and the relational, because all procedures are supported by the emotional connection established between patient and psychoanalyst. Thus, transference and countertransference can be present at any given time.

The process of analytical work requires being alert for this technical axis; the error rests in not being aware of transference, assuming that it is not only a phenomenal manifestation, since whether it is recognized or not, it produces effects, and it is in the field where the reality of the unconsciousness is acted out. It is indispensable to reflect on transference effects in the process of analysis or psychotherapeutic work when working in an institution with children, taking into account the abyss that exists between discourse and practice. Under these circumstances, how can an ethical position be maintained which is commanded by the abstinence rule that even Freud, after having wandered on different paths, elevated to the level of commandment as a universal law for clinical work?

By linking theoretical and technical approaches with clinical work, this paper seeks to open questions and query evidence. How should we relate the transgression of the abstinence rule and the impossibility of withstanding transference with the desire of alienation, the analyst´s anxiety and the failure of analysis? And how to set boundaries in the process of upcoming analysis knowing that singularity is simultaneously a condition and risk of analysis, just as all psychoanalytical ethics? Finally, we will mention the importance (Akhtar S, 2013) of how the analyst reacts to the continual silence, called “listening to silence,” of his/her patients, their nonverbal communication and the countertransference that occurs.

Fiffy, Auestad and Torhild (1983) asserted that there has been far more discussion about transference in child analysis, as with countertransference. They propose the use of the analyst for different emotional reactions and responses to the child´s communication that is only partly verbal, but also nonverbal, on a symbolic level, with play and bodily expressivity, apart from language. Through action, drawing and mobility the child will have better possibilities for penetrating into conflict-laden scenarios, when the child has no words.

Hogar Dulce Hogar

Many governmental and private institutions exist in Mexico that make an effort to provide help to homeless children. Integral Familial Development, abbreviated as the DIF in Mexico (Departamento de Integración Familiar, 2013), transfers homeless children under the age of eighteen to alternative living places.

One of these institutions, offering specialized psychological attention as well, is called Hogar Dulce Hogar (2013). Founded August 15, 1985 in Mexico City, it is a home for up to 73 children ranging from newborns to eighteen-year olds. These children have diverse backgrounds; some came off the streets, others from homeless shelters for abused or neglected children, and others simply can no longer be cared for by their families. It relies solely on volunteers and donations to continue to provide educational, physical, nutritional and emotional support to the children who live there year round. In its 27 years of existence, it has given food, clothing, education, medical and psychological attention, various forms of recreation and a household to homeless children.

Hogar Dulce Hogar is an Institution of Private Assistance (I.A.P.), member of the Board of Private Assistance of the Federal District (Mexico City), a branch of the Government of the Federal District, which assures that these organizations fulfill pertinent laws and verifies that they provide quality services according to a well-established mission. Likewise, the Board of Private Assistance guarantees transparency for those making donations to these institutions.

Some of the children accepted by the Hogar Dulce Hogar Foundation, I.A.P., have been abandoned: others come from shelters—for the homeless, for battered women or for terminally ill women.

Hogar Dulce Hogar aims to be a source of security, development, growth, happiness and love for minors whose integrity is at risk. Its objectives are to give the children a space which covers their basic needs for food, health, clothing, education and emotional development, to offer them safety and legal protection and increase their capacities and abilities to achieve social change.

The homes’ line of action consists in creating a world where minors will become adults who form loving, responsible, respectable, dignified and honest families that transform society. To achieve this, the minor is diagnosed upon arrival in order to design a plan that contemplates the following programs:

Education: An area that does opportunistic diagnoses to individually determine educational projects favoring the holistic and personal development of each child. Psycho-pedagogical: Diagnoses, therapies and periodic evaluations are done by way of updated programs. Social: An area that focuses on incoming children, transferals, socio-economic studies, visits, interviews and personalized follow-up. Legal: A legal space where each situation of the minors is followed. Health and Nutrition: An area that supports care giving, accident prevention, dental programs, vaccination control, medicinal dosage, nutrition and development. Artistic Recreation: An area that oversees activities generating support and entertainment in the children´s activities. Social Service: The department in charge of assuring that established regulations and processes for the children´s attention are followed.

Hogar Dulce Hogar Foundation also accepts brothers and sisters, that is, any minor whose parents cannot carry out their role. Keeping siblings together allows for certain family continuity. There is no time limit for the children´s stay; the foundation is about to transfer fifteen-year-old girls to a new space where they will receive more education to continue becoming self-sufficient.

The Child Psychoanalyst in Hogar Dulce Hogar

Salles (2001) confirms that a child psychoanalyst needs to contain children´s impulses, deeply understand their reasons and motives and be capable of offering continence, support, clarification, confrontation, interpretation, games, dreams and drawings which allow the children to express their conflicts. Isaias (2001) considers it important to organize and understand each child´s circumstances, particularly in adoption processes, at the start of the treatment before the therapeutic relationship has been established. In order for this to occur, initial resistance must be overcome, for this motivates the patient to continue treatment.

The psychoanalyst who treats deprived children living outside their family receives multiple transferences. She/he constantly confronts negative therapeutic reactions, that is, resistance to the cure instead of progress. On many occasions, the analyst works straight through the day and has his/her office within the institution. S. Freud (1923) mentions that in some patients all partial resolution should have as a consequence a bettering, or a temporary disappearance of symptoms, which causes a momentary increase in their suffering and their state worsens during treatment. Whether it is because the repressed returns, the patient does not renounce fixations or she/he wants to demonstrate superiority over the analyst.

In Hogar Dulce Hogar children may encounter their therapist outside of the office; they identify him/her as a responsible adult, as a doctor or teacher, a friend, someone who perceives them as behaving well or poorly. They even hug their therapist as she/he walks around. Perhaps also as the idealized father or mother they have been deprived of. Heineman (2001) considers this to be one of the great dangers that the child psychoanalyst can experience, since she/he is obligated to shift from a professional role.

In the private space where the analyst offers the service, only those needing treatment arrive, those who have that privilege. The psychoanalyst is there in the center of the group, a place of evidence where the parents are not, where the children are looked after and cared for by others. The psychoanalyst sees those children who call the attention of the caretakers, called “aunts.” This gives these children the space to express their fantasies, dreams, fears, anxiety, hope and despair, the possible naming of their sexuality; giving opportunity for control games and frame-breaking.

The analyst has multiple commitments: with patients, the institution and his/her own ethics. If she/he is a recipient of a secret that needs to be revealed, what should be done? Who should be protected? The child, the institution, or the analyst? The frame needs to be very clear: the schedule, number of absences that cause suspension of treatment and costs, among others. What about the rules? Who makes them: the institution, the psychoanalyst or the children?

Children in this frame are a vulnerable population; they have been disconnected from classic cultural and societal norms, and it is often common for them to want to control or impose their own way of binding. The analyst has to consider the vicissitudes in frame-breaking. If the children are accompanied, what does one do? Does the analyst accept them? Is that frame-breaking? One brings the child; the patient does not come voluntarily; should one go get the patient? Or is it tolerated when they do not come for their session?

The analyst walks the institution´s halls, she/he discovers a lot of things that the patients do or provoke; she/he discovers what happens with the children outside the office. Exterior reality limits the process of the intersubjectivity of the word in relation to the analyst. Heineman (2012) wrote in Psychoanalytic Social Work that the trauma of child abuse is magnified for children placed in foster care. The disruption, disorganization and discontinuity experienced in foster care further extend the trauma of abuse. Effective treatment of foster youth must prioritize the basic need for children to experience continuity, stability, and permanency in attachment to healthy adults. Short-term, symptom-focused interventions are inappropriate for this population of ethnically diverse, socioeconomically disadvantaged, underserved, multiply-traumatized youths with complex psychiatric comorbidity. He described a long-term, psychoanalytically oriented, relational play therapy intervention for foster youth.

Supervision

In supervision, the analyst revises his/her notes, the individual work, what is done within the office at the institution. It requires reviewing previous material; as such, she/he reads the words, reads what was said by his/her patients, those who overwhelm, attack, use him/her for identifications and projections; those who paralyze so she/he cannot work, those who abandon him/her, just as they were abandoned; they do not allow the analyst to be in silence to think. They control him instead of it being the other way around; the doctor is lost in discourse and children´s games.

The analyst dares to tolerate affection and constant company. There is more than one child analyst in the institution and the children know this. They do not choose what analyst to see, one is assigned, but they comment among themselves what is said in the sessions. There is a social image of each therapist, and the children tend to compare them. There is a good one and a bad one, or both are bad; the children put together this specular image of the analysts and unfairly evaluate them. Analysts are vulnerable in that way. The children can compare the analysts, challenge them, and destroy each other by using the specular image of their analyst.

Supervision is a place for learning how to think differently, says Grinberg (1986). When theory and clinical work are integrated, increasing the analytical instrument of the supervised analyst is desirable. Experiential learning during supervision is a process occurring both in the supervised and in the supervisor. They are transformed into observers of an experience enriching both of them. This is the process for the experienced analyst whose objective is to train the other.

Wallerstein (1981) stands the focus on the happening of the supervision than of the analysis being supervised and his six fold schema was devised as follows: 1.-resistences and its transference, as discerned via the supervisor’s process of notes based on oral or written material, made available by the student analyst in the supervision hour; 2.-the analyst’s understanding of the analytic material, how it hung together in his mind; 3.-the analyst’s activity, or what the analyst did; 4. -the supervisor’s understanding of the technical analytic issue; 5.-the supervisor’s understanding of the analyst’s personal involvement and his interventions and 6.-the analyst’s response to the supervision hour, and the evidence of the impact of the supervisory teaching of the dyadic and triadic situation.

What is privileged in the supervision? Conflict, affection, the unconscious that is heard, the binding, the adaptation? Conflicts falling upon the analyst treating deprived children—what they suffer and fear—are worked out. What she/he is allowed to hear or speak to benefit the patients.

Salles (2001) confirms that a child psychoanalyst needs to contain children´s impulses, greatly understand their reasons and motives and be capable of offering continence, support, clarification, confrontation, interpretation, games, dreams and drawings which allow the children to express their conflicts. Enactment control is very important; the children act and provoke the analyst´s acting in order to remove him/her from a professional role; any enactment will be useful to treatment.

Clinical Cases

In this chapter three life stories will be presented, that is, the historical life of three little ones who have lived in the orphanage for several years and have been sent to psychotherapy.

Vignette 1: The Daughter of the Dead

We will call her M.; she is twelve years old, just about to enter adolescence. M. was sent to psychotherapy due to her fears and difficulties in adapting. In effect, M. is afraid, very afraid. She is afraid to be alone with her analyst, so a girlfriend two years younger brings her to the session; she says she cannot be alone; she always has to be with someone. She feels alone with her analyst. She distracts her doctor´s attention; she engages him to avoid confrontation. When she brings another friend, the analyst is insecure, powerless. She asks to play with monsters, with dead things.

Her parents died in an accident, and she was beaten by the family that adopted her. M. survived her parents when she was very young.

Does she not want to be alone because the doctor is the dead one? Or because she/he could kill M.? In the hallways of the foundation they say there is a dead woman present. M. says she can see a lot of dead people. She claims to have seen her mother´s spirit once. The analyst mentions that he believes her; her idea is validated so that she can be accompanied while they work on her anxiety about living, separation and reunion. She is not psychotic, just very prone to tantrums. She is just a girl who is very afraid.

How can one work with what threatens binding with the analyst? How to work with a girl who does not want to be there, who arrives for and leaves the session with ambivalence? When she has had to be alone, she stands in the doorway of the office and peers in. She makes the analyst follow her so he leaves the therapeutic space and goes to the patio where there are other girls. If the analyst stays put and M. misses her appointment three times, the patient cannot be seen anymore.

During supervision the girl´s fear of abandonment is revived, the fear that she no longer wants to continue treatment, the fear that M. can symbolically kill her analyst. From passive to active, M. can lash out and go from being victim to being victimizer. Her adolescence gives her strength. She is becoming a woman.

The analyst says that M. makes him feel unsafe in the sense that, “She challenges me all the time, she doesn´t want to be alone with me. Melancholy is always present. The only time she came to her appointment alone she did not pay attention to me; she possesses something that is dead; she knows about the dead; and I´m not dead.” He asks himself if something has to die. The analyst does not want to lose the opportunity to continue working with M., so he has taken advantage of the time, even if other girls are present; he and M. talk about her fear of being alone and of being abandoned like when she does not come play, giving her the opportunity to choose.

Is M. depressed? Does she feel guilty about surviving? Scared to keep living without her parents? Could she be adopted by another family? The uncertainty goes beyond that. Garma (1992, p. 411) mentions that infantile or adolescent depression is not easy to detect; it involves the ego and how it can defend itself from attacks both of the external and internal world, where all the persecutions making up those contents referring to the superego and id come from. Supervision allows the analyst to understand the importance of feeling fear as a defense and of validating the necessity that M. comes to her appointment with someone. Not only because she is afraid, but because it is her way of explaining it to herself: her internal states, feelings, and beliefs. Even if it generates a perturbed and fantasized relationship, it can be established as such. Work will be required to unravel the unconscious where the other is present—and the others who are no longer here but who have remained bound to M. in her particular style.

The analyst hopes to establish an impending connection. M. requires certain timing; she needs to confirm the certainty and usefulness of the session in order to offer up what she feels. The analyst could go from a sense of insecurity to security, helped by transitional objects such as friends, supervision and his own ego regulating countertransference affection by connecting with fantasies of the omnipotent doctor who can take care of all his patients.

Dupont (1988) demonstrates how a psychoanalyst’s work implies a physiological, transitory and ego-related dislocation between the living part that returns with the patient and the other part that observes the process of both participants, as well as including the psychoanalyst´s tolerance factor as knowledge of oneself and of the therapeutic ego, acquired during professional activity, made up of a specialized area of the mind within the performed therapeutic function.

Vignette 2: The Girl-Mother

The second case we would like to share refers to a teenager, age 14, whom we will call K.A. She is the mother of a healthy girl, age two and a half. Both of them live at the foundation, which makes an effort the keep families together as much as possible, a unique feature of the organization.

K.A. was raped by her stepfather; it was only six months later she realized she was pregnant. K.A.´s mother did not believe her (or pretended to know nothing); she even beat her for telling the truth. She arrived at the DIF because K.A. told a neighbor where she lived with her mother and stepfather. The neighbor helped her leave the house and she was directed to another institution; it turns out that K.A.´s mother has not looked her for the last three years. The stepfather went to jail, and the mother accused her daughter of causing her economic support to be taken away; oedipal issues that have been consummated.

K.A.´s baby was born full-term. They received proper attention during the birth. Her family members were not present, but she and the baby were sent to another institution where they took charge of caring for mother and child. Later on the Hogar Dulce Hogar board took over. There was a petition to put the baby up for adoption, but the mother claimed she preferred to be close to her daughter.

K.A. is an adolescent who exasperated her psychoanalyst in the beginning. It started with a strong, negative transference that carries the fear of the death drive, which cannot be symbolized. She was quiet for a long time. It took five whole sessions until she was comfortable. Constant questions were necessary so that she dared to speak. Her distrust was very obvious. When she spoke, she told stories and confused her analyst with fantasies.

In the fifth session she started talking about boyfriends and men; when the forty-fives were over, she asked for more time, but simultaneously said, “It´s over, we´ll leave it for the next time when I´ll tell you more.” She leaves her analyst waiting so that perhaps next time she has something more to tell him, so that he will not leave, so that he waits for her, so that he will not hurt her and she can keep coming back. Moreover, she says, “no one wants to be seen; it´s better you don´t see me. But don´t go.”

K.A. is both adolescent and mother. She says she could be her daughter´s sister and her own mother, which would be the mother of her child, and that the father´s child is her own father. Everyone has a double role in the family. Her confusion lies in her reality and her confusion is her own story. K.A. wants to go back to look for her mother; she seeks identification, to be integrated and loved in the family again. Nevertheless, she knows that her mother does not want to see her, that she would kick her out for having taken her partner away from her, since he is in jail because he raped K.A.

She talks about the following dream: “I´m in the foundation with my mom, my daughter and a male cousin and they are chasing us inside the foundation; we escape, I´m running and I can´t get away; they grab me and rape me and I wake up.” And she says, “You look like my cousin.” The analyst is the cousin! Is he the rapist who invades her privacy? Is he the man who lets her escape? Rape as an elaboration of her precipitated sexuality. The dream confuses the analyst with the ambivalent part that K.A. shows him.

What is the analyst guilty of? Of being a man, of being sexual, of being able to live outside the foundation? The patient offers her experience, fear and desire. She keeps many secrets: not saying who she is or what she really wants. She talks with several friends; she leaves him worried about her disorganized, split internal world, repressing the unpleasant memories of her childhood.

The daughter is sociable and happy, which makes K.A. proud of her. K.A. wanted to play during the session; she says, “Playing is like Angry Birds; they are the fears that are locked up in cages and need to be released if they take away the things you want to get back. They took things away from me and I´m here and angry.” The analyst makes her feel she wants to liberate her daughter, but it is herself. “It makes me feel,” the analyst says, “certain happiness when she challenges me, although she avoids going more deeply.” When she manages a symbolic association, the analyst is content; he feels that he gives her tools to understand her life in a different way; that is how he takes care of her so she will not go. Similarly, she seduces him.

In supervision, the analyst says, “I felt like I was the stepfather, the one that raped her, the one who betrayed her.” And at the same time it seems like she wants him to defend her from other men. “I feel like the patient envies my freedom, the fact that I live outside.” A double role for the same person. During supervision he discovers the male desire he feels when faced with the woman, the potential for a family that K.A. offers.

Vives (2013, p. 23) outlines the dynamic power of unconscious fantasy and how difficult the restriction of the drives that push men toward nurturing women can be, just like the tendency to dismiss the person who impedes that aspiration. Equally, the universal tendency to become the father of the primal horde, be the law and exercise absolute power. These Freudian hypotheses postulated in Totem and Taboo are two of the most important constituents of culture, of the law, which are the prohibition of incest and parricide (Freud, 1913).

What happens to the male analyst when he listens to gender in a dual situation? How does he get trapped in his drives?

The analyst will need to detach from the seeming enactment of the law during supervision. From not repeating the destiny already marked in his patient. The analyst says, “Now I have won her confidence so she tells me some of her secrets.” She is a patient who lies while she plays, and this helps the analyst to discover her. Talking about her daughter tires her, makes her sleepy. The analyst is worried about her being a good mom. Both of them yawn, they grow tired of talking and tolerating the ambivalence of obligatory motherhood, of aggression incarnate. They prefer to play at drawing people; the chosen game is called “guess who,” where people are designed as one would like. The characters are created at will, whether they are men or women, of any age; this allows the possibility of trusting them.

The analyst has several risks in real life, since K.A.´s daughter is very pretty and she walks up to him constantly in the hallways. The analyst´s fantasy is to be the one who takes care of them and protects them from exterior dangers and from his own aggressions. During supervision, the analyst discovers his desire to be an adoptive father and form the perfect couple. The fear exists of not being oneself, of losing the boundaries of one´s own analytical ego.

K.A. does not trust the institution, not the teachers or the adults or her peers, but little by little she approaches her analyst. By making her laugh, he is able to ask her to talk about her true thoughts. It is a task that generates anxiety and fear of abandonment, revenge and disillusion. She feels guilty about being and about not being. She calls him “friend” and he reinterprets this as her analyst friend. Trust and mistrust go hand in hand. The unwanted daughter is her own daughter.

Vignette 3. Two Cut Bodies

They are brother and sister: she is four; he is six. Both of their bodies are marked from the beatings their biological parents gave them. The parents were reported and subsequently imprisoned. After the sentence, two years ago, the children were sent to Hogar Dulce Hogar via the DIF. They are waiting for the papers to go through so they can be adopted.

The two of them are together as much as possible. However, at the home, boys and girls sleep in separate rooms. The institution offers each of them a separate weekly psychoanalytic session. A foreign couple has chosen to adopt them and together they play with the idea that they want to change their names. They wish for a better life. The legal process of adoption has been going on for a year with no end in sight.

She is a small girl with big, wide eyes who comes to her session and pretends to be asleep. Sometimes she comes in, but stays at the doorway. She does not know why she will not come in, but when she leaves, she says, “Good-bye, Doctor ‘Pun’ (fart).” She is very fearful, constantly distrustful, although she smiles easily. After three sessions of not talking and just standing at the door, the analyst asks her if she wanted to bring her brother, who is also his patient. Garma (1992) mentions that by repeating traumatic events for a child, these can be elaborated in transference, mitigating the mark of the event or traumatic complex, adding that in child psychoanalysis the person who verbalizes the action or transference and its constructions is the analyst, and it is s/he who suggests the memory or the early experience that is then elaborated on here and now.

Both patients came and the girl could play at their being parents who hit the analyst son; they played at beating him symbolically. The analyst played freely, saying that they were bad adults. And the analyst tells them that it is hard to receive abuse and give it, too. “What she makes me feel,” he says, “is a lot of tenderness; I enjoy taking care of her.”

It becomes a challenge for therapy; supervision allows the analyst to think. The analyst wants the children to be well, not to be hurt by anyone; they have experienced a great deal of suffering since the boy was only four years old. He feels that the analyst is a threat to them; he frightens them. He is the wolf, unseen but present. The analytical situation is threatening because it is private, separate from the rest of the children and confidential. Tolerance in the face of frustration is an important tool in this situation. His conscious handling of the situation is to not take on the role of the adoptive father. The analyst is warned that it is not worth it to change his role to that of protector, caretaker, father (not stepfather). Fiffty (1983) mentions the importance of verbal and nonverbal language in child psychoanalysis in order to symbolize their products.

It is necessary to reiterate that children have been adopted by the institution, or they will be later adopted by a couple. Garma (1992, p. 408) considers that the basic situation of the adopted child lies in a masochistic link to objects, and this constellation will be repeated throughout life; particularly in the transference link. The analyst suffers intense interference and countertransference when s/he identifies with and submits, along with the patient, to this primary masochistic situation. Nevertheless, the depth of the interpretations and the search for insight is different from what is achieved in an institution as compared to the psychoanalyst´s office.

Brother and sister must defend themselves alone; it is not useful for the analyst to defend them. Their history is violent; the analyst contains and respects that history. Sibling therapy works well with them. Lesser (1978) speculates that this kind of treatment, used with brothers and sisters, is valid and useful, explaining that the influence that siblings exert on each other maintains a symmetric relationship between them—of love and rivalry—that takes them away from generational conflict in such a way that the analyst becomes the doctor who cures, s/he who can help both of them.

In supervision the facility with which the analyst can slip into enactment, always a risk, is examined. This is playing the role that does not belong to the analyst, unconsciously assuming the position of the protective or adoptive father who feels guilt and the need for vengeance due to the aggression the patients received, or that of the director of a new life for the little ones. The brother and sister are together, survivors of their own destiny. Patients who are adopted are often highly resistant to exploring this fact in psychotherapy. Adoption exerts profound effects on identity formation, object and self-representation, superego formation and sexual identity (Brinich, 1990).

The girl says, “The scar hurts,” and she shows her arm; that is what she tells her analyst, her brother and her adoptive mother. She says that her future mother puts cream on the scar and she feels better. The girl says that the beating made her feel that she recuperated something, re-strengthening her identity as the beaten daughter. The character is recognized because of her scars. The analyst´s stay at the institution is temporary; he will be present in the children´s lives for a time and then they will go on their way, carrying what he could offer them, some of their new tools, so they can think about and see themselves differently. That will be the therapeutic achievement.

Discussion and Conclusions

The psychoanalyst´s task is to listen to psychic pain, detect and treat it with his/her means by elaborating, contemplating and returning to the patients something of that unhappiness and something of that possible happiness, from the patient´s transference, utilizing countertransference by working on the effects of this listening during supervision. Even when working in an institution with very deprived patients, analytic postulates allow the analyst´s role to fulfill its function.

Working with this population can imply infantile trauma, abandonment, extreme violence and family de-structuring which affects the development of the child´s psyche, with all the social connotation this implies; multiple deprivation and, in the end, the simulation of rescue that the foundation performs via adoption. The attention offered by the psychoanalyst working within the foundation is very worthwhile, although limited.

The most pervasive phenomena observed in adoptees is the intense belief that they are unwanted and defective, and their repeated efforts to prove it (Brinich, 1990). Patients who are adopted are often highly resistant to exploring this fact in psychotherapy. Adoption exerts profound effects on identity formation, object and self-representation, superego formation and sexual identity. A pivotal way to traverse the patient’s resistance to speaking about this experience is to understand and explore the transference-countertransference relationship as it brings to life the patient’s internal experience.

This includes feelings of defectiveness derived initially from having been relinquished by biological parents after compounded by unconscious identifications with defective biological parents, by self-blaming to excuse the action of rejecting biological parents, and the negative perception of biological parents that are projected onto the adoptee.

Children who have experienced multiple traumatic circumstances may come to view the therapist as a monster since it is too much of a burden to view himself as one. Chronic feelings of unworthiness could result in a variety of negative transference to the therapist, including the patient’s belief that the therapist is disapproving and critical of his/her assumed defectiveness, that the therapist is unworthy and defective as he believes he is and, that the therapist lacks vision to the extent he sees the patient as a person of value.

Children, all of them, have a special anger dynamic that can be projected, and displaced onto the therapist. Driven by this dynamic, the patient may come to transferentially view the therapist as rejecting, reflecting his own projected self-states as well as his expectation that others will resemble. They can be invited to put into active form the loss they were forced to endure passively.

The clinical ability in understanding transference and countertransference enactments provides tools to enrich meaning and accessing adoptees’ conflicts. Skolnikoff (1997) expresses how psychoanalytic supervision, through self-inquiry, can expand his thinking about the supervisorial process and the use of his or her emotional reaction to understand his or her patient.

In conclusion, we would like to recall the affirmation made by Rascovsky (2012) where he states that the multiple obstacles to achieving happiness are also the confirmation that it is easier to experience disgrace and suffering. That humans are happy is not necessarily in the creation plan.

References

Akhtar, M. (2012). Play and playfulness: developmental, cultural and clinical aspects. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 72, 421-424. (doi:10.1057/ajp.2012.23)

Akhtar, S. (2013). Psychoanalytic listening: Methods, limits and innovations. Listening to silence (pp. 25-56). London: Karnac Books.

Axelrod, R. (2006). La maternidad y sus vicisitudes. In C. Zelaya, Y. Mendoza, & E. Soto E (Eds.), El cuerpo femenino y sus fronteras (pp. 89-98). Lima: Siklos.

Bible. (1985). Éxodo: Mishpatim 22:21, Deuteronomio: Rei 14:27 & 16:9, Ki Tavó 6:12-13 & 27:19. In Jewish Publication Society Tanakh (Eds.), The Holy Scriptures. Philadelphia, Jerusalem: Jewish Publication Society.

Brinich, P.M. (1990). Adoption from the inside out. In D. Brodzinsky., & M. A. Schecter (Eds.), Psychoanalytic perspective. In the psychology of adoption (pp. 42-61). New York: Oxford University Press.

Bion, W.M. (1967). Notes on memory and desire. The Psychoanalytic Forum, 2(3), 271-280.

Brinch, P. (1980). Some potential effects of adoption on self and object representation. Psychoanalytical St. Child, 35, 107-133.

Bowlby, J. (1969/1982). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: NY. Basic Books.

Casamadrid, J. (2001). Algunas reflexiones sobre el proceso de adopción, la conspiración del silencio. Cuadernos de Psicoanálsis, 26 (1-2), 66-74.

Clausen, J.M., Ruff, S.C., Heineman, T.T. &Von Wiederhold, W.(2012). For As Long As It Takes: Relationship-Based Play Therapy for Children in Foster Care. Psychoanalytic Social Work, 19, 43-53.

Dupont, M.A. (1988). El factor de tolerancia. In M.A. Dupont (Ed.), El ser psicoanalista, pp. 112-121. Mexico: Lumen.

Feder, L. (1975). Hacia una teoría del paciente deseado y no deseado como criterio de analizabilidad. In APM (Ed.), Analizabilidad. Monografías. México: Manual Moderno. pp. 88-110

Fiffty, P., Auestad, P., & Torhild L. (1983). Countertransference-transference seen from the point of view of child psychoanalysis. Scandinavian Analytic Review, 6, 43-57.

Foster care (2013). Foster care. Retrieved June 26, 2013 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foster_care

Foster care alumni of America (2013). National facts about children in foster care Retrieved June 26, 29013 from http://www.fostercarealumni.org/resources/foster_care_facts_and_statisti…

Freud, A. (1927). An introduction to the technique of child analysis. In A. Freud (1964) (Ed.), The writing of Anna Freud. Vol 1. New York: International Universites Press.

Freud, A. (1936). Ego and the mechanisms of defence. In A. Freud (1964) (Ed.), The writing of Anna Freud. Vol 2. New York: International Universites Press.

Freud, A. (1942). Young children in war-time. A year’s work in a residential war nursery. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Freud, A. (1945). Reports on the Hampstead Nurseries 1939 – 1945. In A. Freud (1964) (Ed.), The writings of Anna Freud, Vol 3. New York: International Universities Press.

Freud, A. (1973). Infants without families. In A. Freud (1973a) (Ed.), The writing of Anna Freud. Vol 3. New York: International Universites Press.

Freud, A. (1973b). Beyond the best interests of the child. Ed. by Joseph Goldstein, Anna Freud, and Albert J. Solnit. New York: Free Press.

Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. 7,125-245. London: Hogarth Press.

Freud, S. (1909) La novela familiar de los neuróticos, Ob completas, Buenos Aires: Amorrortu. Tomo IX, pp. 213-220.

Freud, S. (1912-1913). Totem and taboo. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. 7, 1745-1850. London: Hogarth Press.

Freud, S. (1920). Beyond the pleasure principle. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. 18, 7-64. London: Hogarth Press.

Freud, S. (1923). The ego and the id. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. 19, 12-66. London: Hogarth Press.

Freud, S. (1946). Collected papers, 2, 289. London: Hogarth Press.

Garma, B. (1992). De la expresión lúdica a la palabra. Garma, B. (Ed.). Niños en análisis, clínica psicoanalítica (pp. 235-242). Buenos Aires: Ediciones Kargieman.

Grinberg, L. (1986). Aspectos teóricos de la supervisión. Grinberg, L. (Ed.). La supervisión psicoanalítica, teoría y práctica (pp. 5-27). Madrid: Tecnipublicaciones.

Heineman, T.V. (2001). Hunger pangs: Transference and countertransference in the treatment of foster children. Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 3(1), 5-16.

Heinmann, P. (1950). On countertransference. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 32, 32-40.

Hogar dulce Hogar. (2013). Fundación Hogar dulce Hogar. Retrieved June 26 2013 from http://www.fundacionhogardulcehogar.org/english/

Holder, A. (2005). Anna Freud, Melanie Klein, and the psychoanalysis of children and adolescents: applications, settings and controversies. London: Karnac.

King, P., & Steiner, R. (1991). The Freud-Klein Controversies 1941-45. London: Routledge.

Klein, M. (1926). Early sadism and its relation to the early stages of the Oedipus complex and the formation of the superego. In R. E. Money-Kyrle, B. Joseph, E. O’Shaughnessy, & H. Segal (Eds.), The psychological principles of early analysis. In the writings of Melanie Klein. Vol 1 (pp. 128-138). London : Hogarth Press.

Klein, M. (1928). Early stages of the oedipus conflict. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 9,169-80.

Klein, M. (1932). Die psychoanalyse des kindes. Vienna: Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag. The psycho-analysis of children. London: Hogarth Press.

Klein, M. (1945). The oedipus complex in the light of early anxieties. In R. E. Money-Kyrle, B. Joseph, E. O’Shaughnessy, & H. Segal (Eds.). In The Writings of Melanie Klein Vol 1 (pp. 370-419). London: Hogarth Press.

Klein, M. (1955). The psycho-analytic play technique: Its history and significance. In R. E. Money-Kyrle, B. Joseph, E. O’Shaughnessy, & H. Segal (Eds.), In Envy and gratitude and other writings, 1946-1963. In the writings of Melanie Klein. Vol 3. London: Hogarth Press.

Krakowski, M.I., & Czobor, P. (2004). Psychosocial risk factors associated with suicide attempts and violence among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services, 55,1414-9

Little, M. (1951). Counter-transference and the patient’s response to it. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 32, 32-40.

Lesser, R.M. (1978). Sibling transference and countratransference. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalisis, 6, 37-49.

Lopez, M. I., & Leon, N. A. (2001). Historia y orientación del tratamiento psicoanalítico de niños y adolescentes. In M. Salles (Ed.). En Manual de psicoanálisis y psicoterapia en niños y adolescentes (pp. 19-60). México: Plaza y Valdez.

Money-Kyrle, R. E. (1955). Normal counter-transference and some of its deviations. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 37: 360-66.

National Center for the prevention of youth suicide. (2013). Preventing suicidal behavior among youth in foster care. Retreived 26 June, 2013 from http://www.suicidology.org/c/document_library/get_file?folderId=261&name…

Orphanage. (2013). Orphanage. Retreived June 26, 2013 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orphanage

Orphans and orphanages (2013). Orphans and orphanages. Retreived June 26, 2013 from http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11322b.htm

Orphan. (2013). Orphan. Retreived June 26, 2013 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orphan

Platón obras completas. (1871-1872). Las leyes. In P.A. Corral (Ed.). Diálogos de Platón libro 11 (pp. 226-232). Madrid: Medina y Navarro Editores.

Raker, H. (1951). Observaciones sobre la contratransferencia como instrumento técnico. Revista de Psicoanálisis de la Asociacíon Psicoanalítica Argentina, 9(3), 342-354.

Raker, H. (1953). A contribution to the problem of countertransference. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 34(4), 313-324.

Rascovsky, A. (2012). El bien-malestar en la cultura, In APA (Ed.). Prólogo (pp. 15-17). Buenos Aires: Lugar Editorial.

Rayner, E. (2000). The british independents: A brief history. Retreived June 26, 2013 from http://www.psychoanalysis.org.uk/britind.htm.

Salles, M.M. (2001). La terapia psicoanalítica del niño. In M. Salles (Ed.), Manual de psicoanálisis y psicoterapia de niños y adolescentes (pp. 389-418). México: Plaza y Valdez.

Sideso. (2013). Directorio de instituciones de asistencia privada. Retreived June 19, 2013 from http://www.sideso.df.gob.mx/documentos/JAP/DirectorioIAP.htm#Introducci_…

Skolnikof, A. (1997). The supervisioral situation; Intrinsic and Extrinsic factors influencing transference and countrtransference themes, Psychoanalitical Inquiry, 17, 90-107.

Steelman, A.J. (1907). Charities for children in the city of Mexico. Ph. D. Thesis. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Tubert, J. (2013). Estudio del tipo de conocimiento que nos brida el psicoanálisis. Tesis de doctorado en psicoterapia. México: CEP-APM.

Velasco, F. (1996). Técnicas para el uso de la contratransferencia. In F. Velasco (Ed.), Manual de técnica psicoanalítica, para quienes se forman en el campo de la psicoterapia dinámica (pp.247-265). México: Editorial Planeta.

Vives, J. (2013). Incesto negación y colusión. In J. Vives (Ed.), Lo irreparable, y otros ensayos psicoanalíticos (pp. 23-42). México: APM- Editores de textos mexicanos.

Wallerstein, R. (1981). A study of psychoanatytic supervisión. In R. Wallerstein (Ed.). Becoming a psychoanalyst (pp. 2-17). New York: International Universities Press.

Welldon, E. (2006). Porqué se desea tener un niño? In M. Zelaya, & E. Soto-De-Depuy (Eds.). La maternidad y sus vicisitudes (pp. 99-111). Perú: Sikios

Winnicott, D.W. (1968). Playing: its theoretical status in the clinical situation. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 49,591-599.

Winnicott, D.W. (1971). Playing and reality. London. Tavistock.

World war II casualties. (2013). World war II casualties. Retreived June 26, 2013 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_War_II_casualties.

Zuckerman, J., & Buschsbaum, B . (2000). Strangers in a stranger room: Transference and countertransference paradigms with adoptees. Journal of Infant, Child and Adolescent Psychoterapy, 1, 9-28.